It’s easy to view Artificial Intelligence through the lens of efficiency and data. But what happens when the “Blitzkrieg” of automation meets the nuanced, emotional world of the arts?

Today we are joined by Michael Reid OAM, one of Australia’s most prominent gallerists and cultural commentators. Drawing on a lifetime of observing how industries shift from the rural mail-runs of his youth in Narrandera to the high-stakes boardrooms of Sydney, Michael explores the quiet, structural revolution currently facing our galleries and museums. Here, he argues that while AI may soon “run” the gallery in the background, it can never replace the human “wisdom” that gives art its meaning.

Jobs go and come. Growing up in Narrandera in south-western New South Wales, the milkman delivered our family pint five days a week. Using the intranet of the day, Mum used to leave him handwritten notes in the house mailbox to let him know if we were going on holidays.

My sister, at the time, had a friend at Grong Grong and Matong who worked in the Postmaster-General’s telephone exchange undertaking the night shift, directing calls. “Grong Grong 243, please, operator…” that kind of thing. Anyway, he listened to every conversation, and apparently, they were a hoot. Those jobs are gone.

Although Siri now listens in, with possibly less glee.

It is likely that in a decade or so, we will have to scratch around to remember the many similar jobs of today that Artificial Intelligence will have expunged. Be that as it may, our hope today is that jobs come from all the expected going.

Dealing with the now, what is widely acknowledged is that the corporate rollout of AI will not be polite, structured, or even fully understood. It will be a blitzkrieg—a swift, overwhelming, roll-right-over-our-economy-and-society offensive. In large Australian institutions, particularly banks and multinationals, early productivity gains will be modest. Sales may lift by single digits—perhaps five per cent—as today’s CRM systems like Salesforce are slowly replaced by yet-to-be-built AI platforms that will take some time to mature.

The first real gains will not come from selling more, but from employing fewer people. Headcount cuts will be the fastest way for boards to “prove” AI’s commercial success. This will be staged quietly, rebranded as “strategic efficiency,” and justified not by what AI can do today, but by what executives believe it will soon deliver. Excessive layoffs, or the over-cutting of jobs, will be deliberate, forcing those who remain to adopt AI simply to survive.

In the arts, the impact will be slightly different but no less real. Unlike the very forward-facing, massive employers such as the banks, job losses across the arts will be quiet, uneven, and mostly invisible at first—but nonetheless structurally significant. Arts redundancies will not look like mass layoffs. They will take on the DNA of roles slowly disappearing.

The larger art organisations, with great reluctance to announce cuts, will simply stop replacing people when they leave. One admin role becomes zero. Two staff become one. Attrition does not headline, and the luvvies are less likely to go to the press as the water in their pot moves slowly from tepid to boiling.

Casual and junior roles will shrink. Interns, assistants, gallery coordinators, and studio administrative managers—traditional entry points into the arts—will dry up as AI absorbs the low-level cognitive work these jobs once trained on. This is the real long-term damage: fewer ways into an industry already skewed toward the well-connected and well-resourced.

The jobs that survive will become hybrid. People will be expected to sell and manage, curate and market, create and administer. Have you spotted all the ANDs here? Acute specialisation will decline; general specialists will survive.

At the same time, AI will quietly widen the resource divide within the arts. Well-funded institutions and commercial art galleries will use AI to become hyper-efficient; small, fragile organisations will use it simply to survive. Individuals without capital, networks, brand, or institutional backing will be squeezed hardest. The same amount of cultural output will be produced, but by fewer people, drawn increasingly from those who already have privilege, education, and access. The arts will not become more democratic through technology; they will become even more elite.

This shift will also change how careers in the arts are formed. The old apprenticeship model—learning slowly through observation, repetition, and proximity to senior figures—will erode. Many of the tasks that once taught young workers how art museums or galleries function will be automated before they can even be learned. The result will be a generation entering the sector with fewer informal skills and far less institutional memory.

At the same time, funding bodies and boards will quietly recalibrate what they value. Metrics will replace mentorship. Data will replace intuition. Reporting will become automated, but expectations will rise. Organisations will be required to demonstrate “impact” with increasing sophistication, even as the human infrastructure required to generate that impact is reduced.

This will place new pressure on remaining staff to become cultural translators—people who can sit between artists, audiences, institutions, and machines. The future arts worker will need to understand systems without being defined by them, to use AI fluently without surrendering authorship, and to preserve meaning in an environment optimised for efficiency.

The AI transition will demand new hybrid skills. Artists will increasingly make work by instructing machines as well as using their hands and eyes. Language, not just materials, will become part of the artistic process. Gallery staff will need numeracy in data, not because they want to become analysts, but because exhibitions will increasingly be shaped by patterns revealed in AI-driven insights. Administrators will move from filing and forms into managing automated systems that quietly run inventory, invoicing, and logistics in the background. Marketers will be less about announcements and more about storytelling that can survive algorithms. Even art handlers will find themselves dealing with tracking software and digital logistics tools. None of this is speculative; it is already happening, just quietly. The net effect will be the same everywhere: less time buried in administration, more time required to interpret, decide, and take responsibility for meaning.

Front-of-house roles will last longest. Client relationships, fundraising, education, public programs, and artist liaison remain human because they depend on trust, intuition, memory, and emotional judgement. These are not processes that can be automated without losing their meaning. People do not build long-term relationships with galleries, artists, or institutions because a system is efficient; they do so because they feel understood, recognised, and valued.

Front-of-house roles will last longest. Client relationships, fundraising, education, public programs, and artist liaison remain human because they depend on trust, intuition, memory, and emotional judgement. These are not processes that can be automated without losing their meaning. People do not build long-term relationships with galleries, artists, or institutions because a system is efficient; they do so because they feel understood, recognised, and valued.

Fundraising, in particular, relies less on data than on credibility and personal history. Education is not simply the transfer of information, but the creation of context and curiosity. Public programs succeed not because they are well scheduled, but because they are well held. Artist liaison is, at heart, pastoral care — managing ambition, insecurity, temperament, and time. These are deeply human negotiations.

AI may assist, suggest, and even prompt, but it cannot replace the subtle social work of reading a room, sensing hesitation, remembering a personal story, or knowing when not to speak. In a world where everything else becomes optimised, these front-of-house roles will become not just the most resilient, but the most valuable.

The paradox is that the arts will not become smaller, but they will employ fewer people to do the same amount of work. More output, less labour, higher pressure.

What will be valued most is wisdom: human insight, client relationships, and emotional intelligence. AI will quietly run galleries in the background—listening, invoicing, updating stock, scheduling payments—while humans handle the meaning of it all.

About Michael Reid

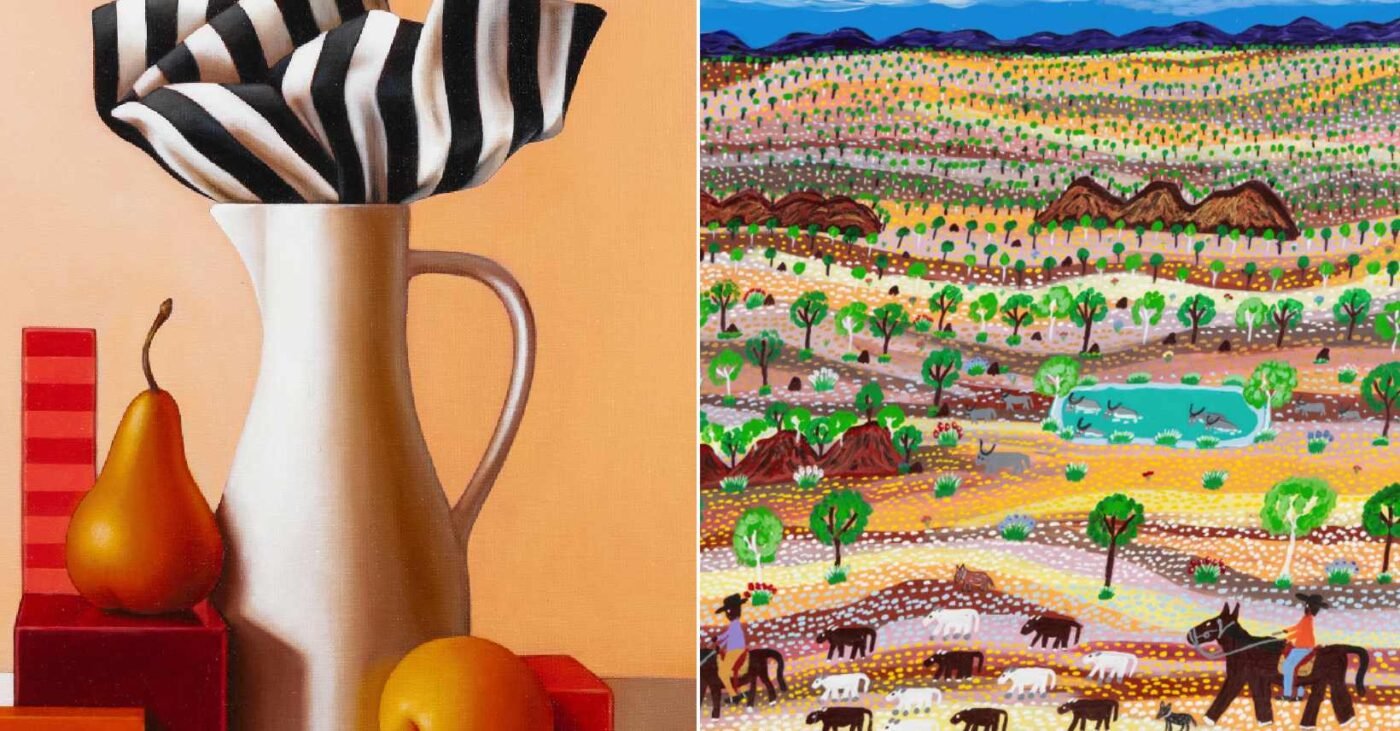

Michael Reid is a leading Australian art dealer, author, and the founder of Michael Reid International. With galleries in Sydney, Berlin, and a specialised “concept” gallery in the historic village of Murrurundi, Michael has spent decades shaping the careers of contemporary artists and advising major collectors worldwide.

A former art columnist for The Australian, Michael is renowned for his sharp wit and his ability to demystify the complexities of the art market. Through his various platforms, including Michael Reid Murrurundi, he continues to bridge the gap between traditional connoisseurship and the modern digital age, championing the idea that while technology changes the tools, the human connection remains the heart of the masterpiece.